The challenge of measuring what truly matters: why I practice social planning

A personal backstory

People often ask me how I ended up in social planning.

For me, the answer goes back to a trip to Nepal when I was 11. That’s when it really began.

For context, growing up, our family holidays were not your typical family holidays. My dad, Stephen Codrington, is an geographer and lifelong traveller, and instead of resorts or theme parks, he would take us off the beaten track, spending time with local people—understanding how they lived and enabling us to experience the sights, smells, and landscapes of other cultures.

Those experiences shaped me. They ignited my love of human geography—and gave me a lifelong sense that how people live in place matters just as much as the place itself.

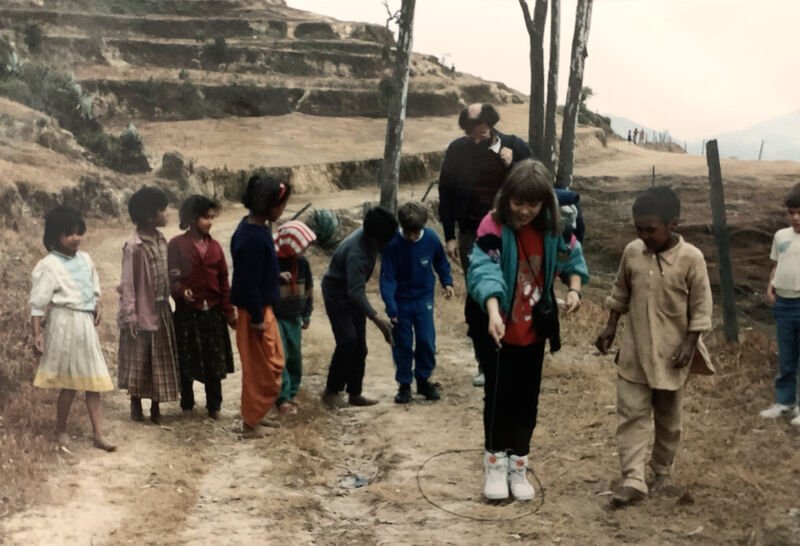

I have a vivid memory of our trip to Nepal in 2011. In the photo my dad took (shown below), I’m at the front, trying to play a simple hoop and stick game that the local children played, with my brother and my dad behind me. We wandered alongside them, laughing, and trying to master the technique. I was hopeless—unable to get more than a couple of steps with the hoop before it tumbled to the ground. They, on the other hand, kept it rolling with ease, barely glancing at it, chatting away and clearly enjoying themselves, bemused at our hopeless lack of coordination, I'm sure!

Photo of the game we played in the mountain villages of Nepal, 2011 [Photo credit: Stephen Codrington]

But what struck me most wasn’t their skill—it was their happiness. Genuinely happy—smiling, friendly, welcoming. Language was no barrier. They welcomed us in and showed us their neighbourhood. They seemed to have so little, and yet the joy that they shared was palpable.

At 11, I didn’t have the words for what I was experiencing. I just knew that the contrast between our worlds was confronting. These children seemed to have so little, yet their sense of contentment was something I couldn’t ignore. I remember coming home to our newly renovated home, and tearing up at just how much we had in contrast to them. I sat on our carpeted stairs and cried.

That contrast—and that feeling—is imprinted in me.

Happily playing on basic playground equipment with my brother, 1987, Gyula, Hungary [Photo credit: Stephen Codrington]

What does it mean to build communities that thrive?

That question—the one that started forming on those dusty village streets—is still at the heart of my work today.

In social planning, we’re constantly asked to measure outcomes. Show the data. Prove the value.

And that’s fair enough. We need accountability. But here’s the catch: the things that matter most aren’t always easy to measure.

Sure, we have measurable indicators like access to healthcare, education, and housing—all crucial. But how do we quantify things like belonging, connection, resilience, and wellbeing? How do we measure whether a community feels safe, supported, and included?

We often end up with proxies: community insights, survey findings, lived experience interviews, qualitative data. And while these are rich and essential, they’re often dismissed as "soft"—less credible because they don’t come with decimal points.

But if we leave those things out, we’re not planning for people.

Example of social sustainability considerations for connection, wellbeing and liveability [Photo credit: Liesl Codrington]

Why social planning matters

If we don’t plan for how people live, connect, move, rest, gather, belong… what are we doing?

I’ve worked on too many projects where conversations centre around efficiency, and maximising economic return. Having the numbers stack up. But the social case is an uphill battle. I can often feel like I am one voice in the room saying "remember the people".

I’ve also seen the opposite: places where careful social design made all the difference. Where a small investment in shared space led to a culture of neighbourliness. Where accessible services and inclusive design changed daily life for those who needed it most. And that's a beautiful thing.

Planning that integrates social sustainability principles doesn’t just benefit communities—it makes developments more successful long-term. A well-designed urban precinct that fosters social connection will be more vibrant, attract more visitors, and contribute positively to economic sustainability as well.

Livvi's Place, an inclusive playground, Canberra, 2013 [Photo credit: Liesl Codrington]

So… how do we measure what matters

There’s been some progress. The ACT Wellbeing Framework. Australia’s Measuring What Matters statement. These are steps in the right direction—towards a planning system that recognises people, not just parcels of land.

But we still have a long way to go.

I come back to those children in Nepal, rolling their hoops with joy. Their lives were simple. But they had connection. Play. Community. A sense of belonging that many new developments in Australia are still struggling to offer.

If we only measure what’s easy to count, we’ll miss what really counts.

Those trips with my Dad and the rest of my family... they really mattered. [Photo credit: Stephen Codrington]

Where do we go from here?

We need to be asking different questions:

Are we designing places that feel good to live in?

Are we making decisions that prioritise people—not just policy targets?

Are we building spaces that welcome difference, not just manage it?

Social sustainability isn’t a layer to be added on later. It’s not a checkbox. It’s the base layer. The thing everything else rests on.

I’d love to hear from you

What drew you to your field?

Where have you seen social sustainability done well—or overlooked entirely?

Let’s start sharing the stories that numbers can’t tell on their own. Because those are the ones that shape the places we build—and the lives within them.